ART ESSAY

Artist KARLA SACHSE in conversation with VANESSA PATEL about paper, politics, and the body as a vessel for memory.

Looking through your catalog, Karla, I’m struck by such a rich body of work. I saw some of it while you were producing it and again at one of your Berlin shows. You’ve used paper in such unique ways! You’ve taken something seemingly fragile and transformed it into something enduring. Why paint on paper, rather than canvas, for instance?

At first, I painted on canvases and boards, but soon I started thinking that other people were better at painting than I was. Changing to paper made it easier to destroy the works later. You can’t do that to a canvas. You can’t tear it up. You can crumple paper and throw it away—which I never did!

You’ve used everything—scraps of paper, documents, ticket receipts, shredded paper, newspapers, paper in all forms.

There is one sentence I recited yesterday at the Free University of Berlin during a talk. It says about paper: “solid stuff and fluid again and often sliding off the hands of the creators”—just describing the material. I liked the idea of using things that were already used, with a history and a story inside them.

Absolutely, every tiny little bit of paper has a story to tell. Was this way of working inspired by your early days in East Berlin?

It was when I met my partner, Joseph, who was already involved in this international Mail Art network [a decentralized global exchange in which artists mailed small artworks to one another, creating connections that bypassed official state channels and, in East Germany, offered a rare and sometimes risky way to reach the outside world] and was making things that could fit into an envelope to protect them and, hopefully, keep them out of the control of the secret service. So, the first things I did were small, and some I never showed during that time in East Germany because they were political. I would cut out newspaper reports and comment on them, and this was dangerous.

That would’ve gotten you into a lot of trouble!

Yes, and I had a son, so I didn’t want to go to prison. But I also did bigger works. I got the opportunity to do my first room installation in June 1989. I filled a room with paper: the walls were covered with blank, beautiful, whitish papers, and the floor was littered with crumpled papers, so you had to wade through it.

Central to this was a tall column of newspapers, the main organ of the Communist Party, which, of course, you couldn’t read there and which almost nobody wanted to read anymore. I could make a statement and still look “innocent,” with “blue eyes,” as we say. “I’m not guilty, I just put these beautiful newspapers in a stack.”

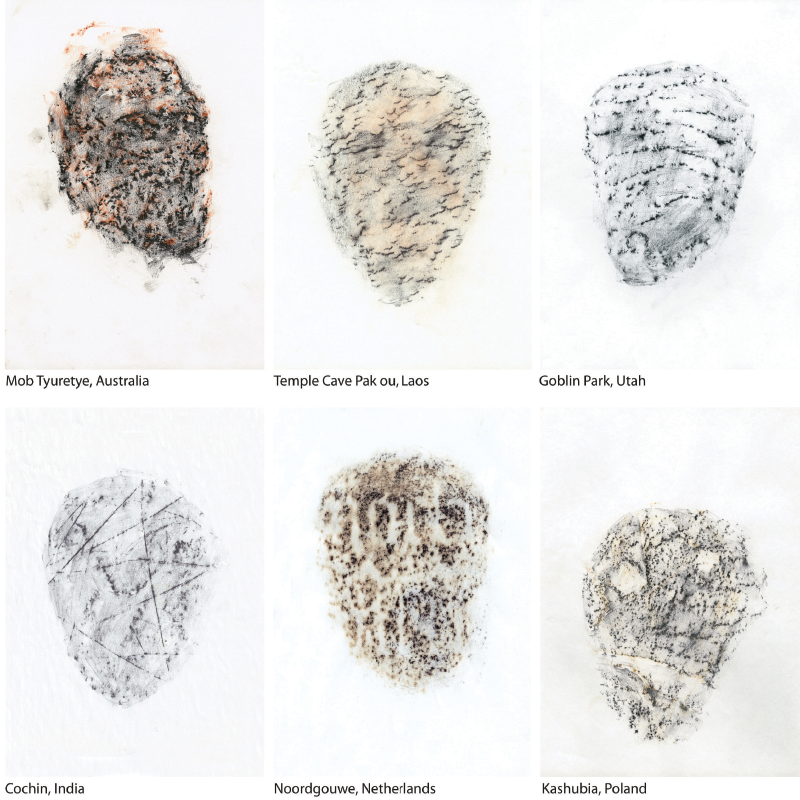

That was really clever. You’ve done extensive work with frottage, making rubbings, and you seem to see images in discarded objects and bring them to life. How do you decide what you want to take a rubbing of?

Where I have my country garden now, there are many large and small rocks deposited during the Ice Age. I thought something must have happened to them when they were brought here by ice. So, I looked at their surface. We humans always want to see ourselves reflected in things!

I placed some paper on one rock, and then you have this surprise. There’s something that looks like eyes showing up, and then you examine by touch, and the stone itself tells you where to stop. But it’s always different from what your eyes have seen.

I did an exhibition called The Hands See Different. The rubbing hands see differently from the eyes, and it’s always a surprise.

You sent me some beautiful, fine muslin cloth some time back, and I used this instead of paper—for example, to rub the ghosts of the place out of the walls of a former power plant in Denmark. The cloth hung and moved in the space, so it came to life in a different way.

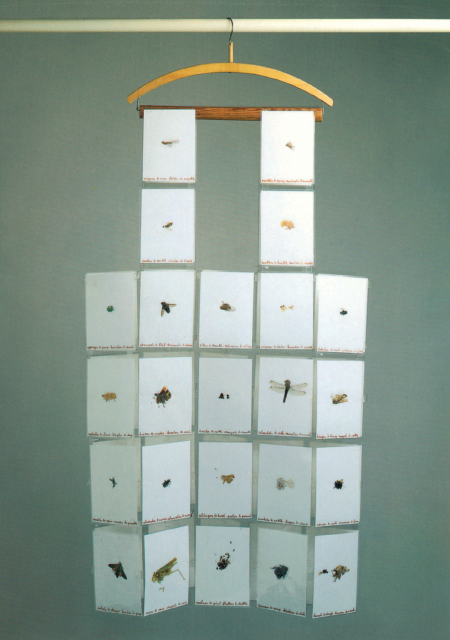

I shouldn’t have a favorite, but my favorite body of your work is Baskets of Experience. They’re woven paper objects resembling body parts, and you explained that each one you made in a different country using the newspapers you found discarded in that place. How did you conceptualize these “vessels”?

I learned how to weave baskets at a Womanifesto workshop in Thailand in 2001. It needed a lot of patience, and I knew immediately I would like to shape body parts from the rolled-up paper.

At that time, there was a big discussion in the media about prenatal diagnostics, the ultrasound, and the doctors had so much control, and that made me furious. So, there in Thailand, I made a uterus, which was part of [contemporary art exhibition] Documenta 15 and is now in the archive of Womanifesto in Thailand. I knew immediately that I would continue working on this.

Wherever I had time—let’s say, a week or more—I started to weave a new object. Before traveling, I would wonder, what do I have to do with Denmark? What do I have to do with India? And I asked my body which part of it would relate most to that special place I was going to. So, for India, I made a longing vessel—a heart—because India is the heart of the world for me.

I was going to ask you why the heart for India, and I know you’ve been there a few times and worked there as well.

When we had the residency in Kochi, Kerala, there was enough time to weave the heart. From the beginning, it was essential for me to include people’s opinions and stories. So, I asked everyone who worked with us or was around us for their “heart” experiences, the pains and pleasures.

They wrote them down on paper and, in front of their eyes, I rolled up the paper—so you could see that it was handwritten, but you couldn’t read it anymore. The secret was kept and included in the basket weaving. This was, from the beginning, another idea of collaboration, which is very important for me.

That’s such a uniquely inclusive way to give them a voice and space while at the same time respecting their privacy and innermost feelings. And again, those vessels are holding their stories.

In 2023, when we had this big exhibition at the Bangkok Art & Culture Centre in Thailand, I had a great opportunity to create an installation. The woven objects hung from the ceiling to eye level, so visitors moved between them.

Many young people were visiting this exhibition, which we don’t often see in Berlin and in the West. You could see that they tried to read or to figure things out—and perhaps to “weave” their own story in response.

What did you want them to feel and experience when they saw these body parts in basket form?

From the creation point, it’s an experience of myself, of my body and mind related to a certain place. But because the pieces have shapes you can recognize, if you have some idea of anatomy, you can include your own experiences. You can ask yourself, what do I think and feel about my own digestion, through the intestine, and mentally?

I love the eyes—the five eyeballs.

Yes, the eyes are very, very special because I did them in Vietnam after talking to war veterans. You cannot ask them directly about their experiences, so I asked them what they’ve seen in their life.

They didn’t talk about the war, but about their surroundings and their life in general. So, these eyes are particular. They represent five different people, and to this day, they’re very touching for me as well.

I know you as an artist, but a big part of your life has been as an art teacher, and you’ve influenced so many young people. What did you gain from it? How did that process help you in your creativity?

In my studio at school, the students did painting. I could help each of them individually with what they needed to know about their work. Of course, I used to expend a lot of energy to prepare all this teaching, but I always had the feeling that I got back the same amount of energy from their being, their youthful being.

Nowadays, it’s great to have a community of young people. When I’m having a show opening, I like seeing young people out there, not just people my age.

Yesterday, I gave a talk at one of the universities in West Berlin to thirty-five students, and I showed some of my work. They’re studying literature, and the seminar was about Concrete and Visual Poetry. Very soon, they started asking very intimate questions about the political situation and other matters related to my work.

They’re all born after the Berlin Wall came down, so they’re not directly affected by that situation. Again, it was an immense pleasure to see these young people watching and being curious.

Karla, your work is multi-locational; you’ve worked and exhibited all over the world. Has this kind of wanderlust come from perhaps living for some time in a closed environment, confined to a space with restrictions?

From the creation point, it’s an experience of

myself, of my body and mind related to a certain place. But

because the pieces have shapes you can recognize, if

you have some idea of anatomy, you can include your

own experiences. You can ask yourself, what do I

think and feel about my own digestion, through the

intestine, and mentally?

I had worked with some underground groups before to change our society. But when the Wall was coming down, it was clear we were going to the Western system immediately, which was not a good situation for many people.

I thought, well, it’s too late for me. I couldn’t go live in New York for a year as I would have liked because my son was small.

But since then, I’ve been to all the continents with projects and within Europe through this Mail Art network. At first, I didn’t want to go to Paris and London so as not to destroy my illusions about them, but I finally went after visiting many other European countries.

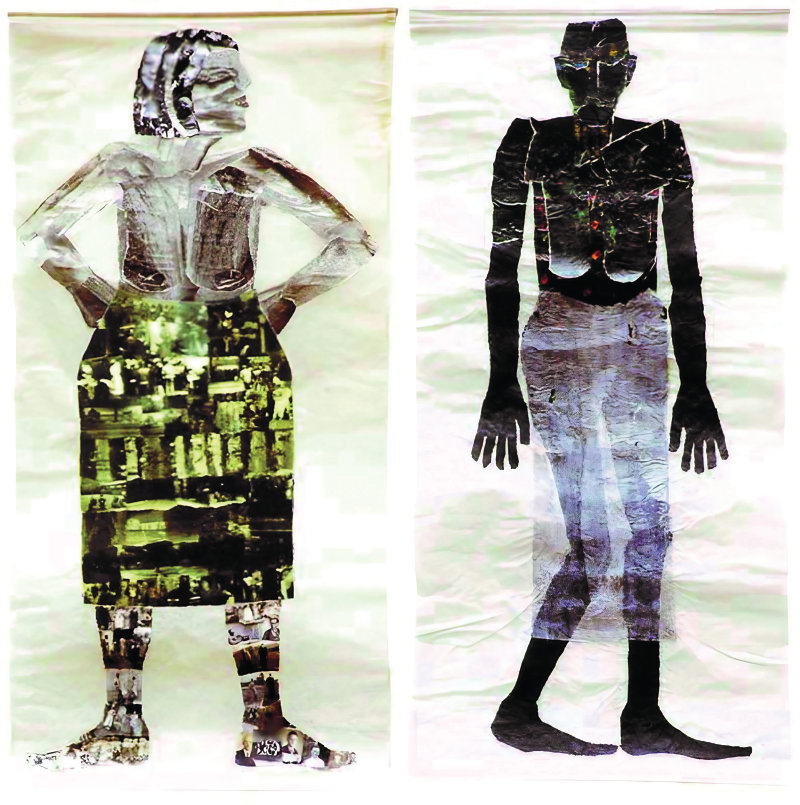

I’ve seen one of the pieces from your work, Settled Down Women, which are full-sized collages of female figures. Can you talk a little bit about that work?

This was an outcome of the Mail Art network. I used to correspond with an artist in Brussels, Belgium. He invited me to a show in the former monastery for nuns in Brugelette.

This made me think about the feminist writings and stories that came from the West, and although I’ve never really had to deal with the problems of patriarchy, I was very much in solidarity with the cause. So I made these twelve matriarchal figures—four white ones representing young virgins, four red ones representing the mothers, and four black ones representing the older women. These represent the holy trinity that existed long before the one in Christianity.

I worked on these for over fifteen days without sleep, and once they were done, I rolled them up and sent them off to Belgium, not really knowing what would happen to them. Fortunately, I had an aunt who invited me to visit her on her eighty-fourth birthday, and I was able to obtain an illegal substitute passport to travel to Belgium. So, I saw the exhibition there in this monastery.

That’s incredible. You made this before the Wall came down, posted them off in a roll, and saw them displayed! That must’ve been mind-blowing.

It was mind-blowing because they were all hanging in one big space, and you could see them from the back as well—it was beautiful, more abstract than from the front.

Later, they were shown in another place in Belgium and in a church in Denmark. When they came back to me, I thought, I’ll never show them again (which I regret), so I sent them to women I knew around the world to display so others could see them.

Your matriarchal figures have traveled out of East Berlin and gone everywhere. Is there anything that you wanted to share that we haven’t talked about?

Yes, in my catalog, there is a statement called “Matter – Language – Space.” I wrote this in 1998, and it’s a bringing together of all my work.

It reads like poetry to me.

Yes, exactly this. You can read it in columns, top-down, or horizontally across the columns, and it still makes sense.

That’s a wonderful note to finish on. I’ve discovered even more aspects of your work, and there’s more yet to explore. Thank you, Karla, for your time, and please continue making these amazing connections.

To discover more about Karla Sachse’s art and ongoing projects, visit her official website: www.karla-sachse.de

Artwork by KARLA SACHSE

Karla Sachse

Karla Sachse is an artist based in Berlin and Herzfelde whose practice spans visual poetry, language-based installations, and memorial works in public spaces. Emerging from the Mail Art movement, she leads col... Read More