CLARK A POWELL shares how a dream visitation ended twelve years of self-imposed exile and revealed the bliss he’d spent a lifetime pursuing.

I got a phone call on December 22, 2025. A piece was required for the February issue of Heartfulness Magazine, and it had to be delivered within three days. During that conversation, the editor seized on something I’d been saying about my experience with Isolation and Solitude and suggested the title above.

For me, it has been a long lifetime’s journey capped by a hard twelve-year final trek to move from Isolation toward Solitude. But let’s start where philosophers tell us to start: by defining our terms. Then we may redefine them.

Solitude and Isolation are not the same. In fact, they are opposites, or at least at opposite ends of a continuum.

Isolation is small. Solitude is large.

Isolation is cramped. Solitude is roomy.

Isolation is bound. Solitude is free.

Isolation excludes. Solitude includes.

Isolation is a human condition. Solitude is the nature of Divinity.

Isolation is alone. Solitude is all-one.

Isolation is misery. Solitude is Bliss.

Solitude is a state of wholeness or oneness that abides whether we are alone or in a crowd.

I spent the last twelve years, twelve long and wasted years, in complete and utter Isolation. I never left the house; I never even left my living room. For twelve years, I saw no other human being in person, except the doctors who refused to treat a human body unless I presented it to them. Over these twelve years, I talked over the phone with a single family member who made “welfare calls” to see if I was still alive over there in New Orleans.

The obvious question is WHY. Why did I, a preceptor1 since 1992, fall into such a state? One Sahaj Marg sister called this family member to ask what had happened to me.

My welfare checker told her that it seemed to her I was just “waiting to die.” That is exactly what I was doing, since suicide was an exit I felt was not permitted to me. For twelve years, I lay on the couch watching TV and waited to die. You see, all my life, I have battled depression, or something like depression. At times, I would drop off the table and just disappear. A lifelong friend from childhood named these times of retreat “Powell Outages.”

The psychiatrists I was sent to had different names for my condition. I saw waves of doctors all the way from the psychiatric diagnostic bible called the DSM2 all the way to the current DSM5. They all tried to help, but each new wave argued that the previous diagnosis was wrong, and I was sent away with a new, more modern set of drugs.

But in every diagnosis, some form of depression was the obvious culprit. I can’t tell you how many pills I was prescribed that were promised to make me “normal.” But for me, they only succeeded in giving me a weird variety of unwanted side effects that those powerful psychotropics are known for.

So, one by one, a succession of shrinks declared my depression to be “treatment resistant.” Not even a series of last-resort electro-convulsive “shock therapy” sessions worked. This is because my condition was one of my psyche, the Soul or Self we all embody. It was not a psychiatric condition.

So, I turned to God for help. But how do you turn to God? During my teenage years, I followed the religion of my parents: Methodist Christianity. But with the Methodist religion, I got nowhere close to the God I was seeking. Nothing wrong with Methodism; it just wasn’t the road for me.

Finally, something changed inside me. In 1969, I got a summer job working as a deckhand on an old Victory ship that carried bombs and ammo across the Pacific Ocean all the way to Vietnam. After that voyage, I returned to Mobile to finish my senior year of high school. But I was not the same person who set out on that voyage. The journey to Vietnam and back had turned me upside-down.

I got off the ship and announced to my mother that I was now an atheist. I could no longer accept this God I was taught to believe in in Sunday School. Mother sent me to our wise and patient minister, Dr. Joel McDavid, and we talked about God every Friday in his office. I never converted him to my new religion of atheism, but somehow all those weekly talks softened my heart toward the idea of Jesus.

The big shift came in May of 1970, when I was about to graduate from high school and take a full scholarship to Vanderbilt the next Fall. I was told by a surfing buddy that some real-life hippies from California were visiting our little Gulf Coast town of Mobile, Alabama—and all they were talking about was Jesus Christ!

So I went to hear what these long-hairs had to say, pretty sure I would defeat their childish faith with my superior atheism born on the Mekong River. I didn’t win that argument. Instead, I found myself answering an “altar call” and weeping at the front of Bayview Heights Baptist Church and “giving my heart to Jesus,” as they called it.

Soon after, I got baptized in the Holy Spirit, and “spoke in the tongues of men and angels” like the rest of that renegade Southern Baptist church at Bayview. Soon, I felt that I had a Calling, and by August, I was so sure that I told my mother I wasn’t going to take the scholarship to Vanderbilt because I felt God was leading me to Liberty Bible College in Pensacola, where I was to become a full-gospel preacher.

My poor mother was just as horrified by this extreme as she had been by my previous announcement that I was an atheist. But this time she didn’t send me to our high-society Methodist minister. She turned for help to the only man I would listen to, Brother Charles Simpson, the charismatic leader at Bayview.

He used to prophesy during Sunday service in the Name of the Lord, and sometimes he’d cast out demons right from the pulpit into the fainting members of the congregation.

But to my mother’s great relief, Brother Charles said this: “Clark, don’t go to Liberty Bible College. Accept the scholarship and go to Vanderbilt.”

So I did, feeling like I was Daniel going into Nebuchadnezzar’s palace. Vanderbilt felt like a hostile place to my newfound faith.

This was the time when the hippies called “Jesus Freaks” were emerging everywhere, and a big revival was flourishing across the campuses of America. It was a different moment in time when I went up to Nashville and started what we called a house ministry on 16th Avenue South, the famous Music Row.

We imagined ourselves like those First-Century Christians right after Jesus ascended, who lived in common, sharing everything and owning nothing, and we were relentlessly “spreading the Gospel.” At the age of eighteen, I was called Brother Clark by my little flock and was considered an “Elder.” It would have been funny, except we were all so desperately certain God was speaking in our hearts. Maybe He was.

By the next summer, everything changed. I’d gotten a summer job selling Family Bibles door to door in North Carolina, where the cognitive strain of maintaining my worldview, combined with twelve hours a day in the Southern summer heat, just broke me. I was knocking on doors and scaring people with my pleas and exhortations.

My parents drove up to fetch me back home to Mobile and to my first (and very bad) psychiatrist, a man who blinked at me in silence for the first fifteen minutes of our thirty-minute weekly sessions and then would utter in a flat voice, “How. Are. You. Doing.” and who turned me into a compliant, shuffling zombie with heavy doses of four anti-psychotic drugs, Artane, Navane, Thorazyn, and Prolyxin.

This piece is longer than I intended, so I’ll skip past a few inpatient hospitalizations, and past my winter in a Zen Buddhist center on Page Street in San Francisco, and at Green Gulch Farm across the Bay in Marin County during the winter of 1981–82.

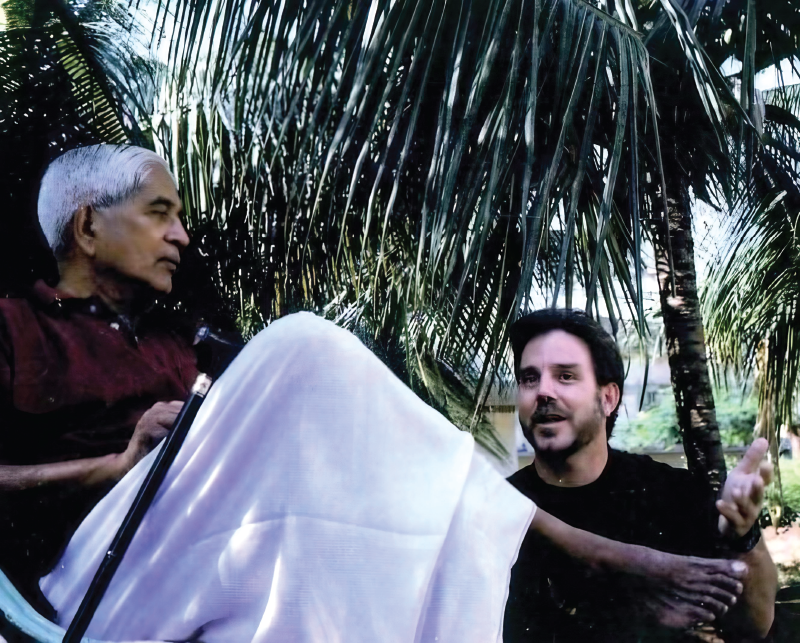

Let’s cut to my first glimpse of Shri Parthasarathi Rajagopalachari—affectionately known as Chariji—at the Molena Ashram near Atlanta in 1992. All I could see was his silver hair as he towered over everyone crowding the steps to greet him.

I had just taken three introductory sittings and begun a new meditation practice called Sahaj Marg. When I saw Chariji, the spiritual guide, or “Master” of Sahaj Marg, I dearly hoped this man would be the one I had been searching for most of my life. I hoped that, somehow, he would be my destiny. During the sittings he gave to the abhyasis2 gathered under the large meditation tent, I began to feel what they had told me, a transmission of yogic energy3 that seemed to be slowly melting away the confusion in my heart.

I was just a two-month-old abhyasi, but there were no abhyasis where I lived in Alabama, so Chariji gave me a sitting and made me a preceptor. I was weeping by the end of this sitting with the Master.

I’ve always been an “all-in” kind of guy, a trait that has both advantages and weaknesses. But I didn’t hesitate to spend all the money I had and follow Chariji back to India. I returned to India nine times between 1993 and 2011, for an average stay of four months per trip.

From my first visit, Master blessed me by keeping me close because he liked the kind of questions I was always asking. These were the questions of a beginner who knew nothing, and for whom there were no rules, no formal niceties, and nothing was out of bounds. I even shook hands with Master to confirm an agreement that we’d always be completely honest with each other. He took my hand and said, “Deal!”

The pinnacle of this close contact, this gurukulam,4 first came in 1997, when Master spent two weeks confined at RK Nature Cure Home in Coimbatore to accompany his wife, beloved Sulochana Mami, and I was one of twenty lucky abhyasis admitted there. That was where our long conversations really began, when Master would say, “Where is that fellow from Alabama? Bring him here. He is one of two people in this Mission [the other being Ferdinand Wulliemier] who can get me talking.”5

The second gurukulam for me happened in 2004. I had been away from the Master, the Mission, and the Method for seven long years, following an argument with Chariji on the topic of Lalaji’s6 guru, of all things, along with the ways I’d made a fortune on the new Internet. (At least I thought these were the reasons I left the Mission. Now I know the real reason.)

A disciple may reject the Master. But a Master, as Chariji told me, is not allowed to reject a disciple.

Thank goodness. During my stubborn and foolish seven-year sabbatical, I kept receiving letters and invitations on beautifully embossed, heavy stationery, signed with a flourish by “Parthasarathi.” The letters kept asking me to return to India.

One day, a letter arrived requesting me to visit a new ashram that had just been built near the Great Himalayan Mountain Range, in view of Trishul and Nanda Devi.

The new ashram was called Satkhol, he wrote. He added a PS: “If it will help, I’ll make my request an order.”

How could I refuse?

On the way, I stopped in New York City to purchase movie equipment. I had the notion that I’d continue recording everything the Master said and did, only this time not in my journals, but on film, so everyone could see and hear what it was like to converse with the Master. I later came to feel that Master only gave attention to a galoot like me because he saw in my heart a deep need to make a Give-Away of his words and doings to anyone who could receive all he gave so abundantly to me.

As we pulled into the tiny Satkhol ashram, Master turned in the front seat and said into my rolling camera, “You will stay with me in this cottage.” I simply replied, “All right, Sir,” not realizing the importance of this invitation or what I was later told, that I was the first Westerner ever to stay in Master’s cottage.

For two weeks, I lived in sheer Bliss, like a family member in the home of the Master, just as Babuji7 said a true disciple should.

And I taped everything, every meal and every conversation, including one at his tiny window seat before a crowd packed behind me and a confusing camera not meant for an amateur like me. That was when Master discussed the lineage of the Masters of Sahaj Marg, all the way to Lord Krishna! My stay in Satkhol was the pinnacle of all my journeys around the world. (To my shame, I was never able to edit some forty hours of raw footage into a finished documentary or series. But I still have them.)

By and by, things changed, as they always do around a Master. In my later visits, the close attention was gone—gone the idyllic conversations, gone the gentle affirmation of his gaze. I now see what I realize he saw: a fellow stuck in a past where he thought he was the teacher’s pet. My ego felt that I was some kind of big shot.

Chariji, of course, saw how that trickiest of all foes to any spiritual aspirant, the subtle “spiritualized ego” that comes into play as one ascends the spiraling staircase in an invisible tower up to a place where the Divine is concentrated. The spiritualized ego is a relentless and difficult and shape-shifting foe. Only love can dissolve it.

The spiritualized ego is a relentless and

difficult and shape-shifting foe.

Only love can dissolve it.

I had already seen how Chariji knew everything he needed to know, sometimes the shameful things I tried to hide from everyone. He saw at a glance something Daaji8 once spoke about, how there was really no so-called inner circle of disciples, but there were workers always found around a Master of caliber to assist him in his own Master’s work.

I lost sight of the burden I was placing on the human being he was, and something that Daaji-Kamlesh Bhaisaheb9 was able to see from the center of that changing osmosis of orbits around Chariji never occurred to me. It never dawned on me that my constant struggle to stay close brought suffering to his huge heart of kindness. I was not considerate enough to relieve Master of the pressure of my presence.

Most abhyasis seem to know that being physically close to a capable Master is not at all necessary for rapid spiritual advancement. He could transform a life with a single glance and did so many times. If you are ready, if you are capable of surviving his full transmission, he can bring you straight to the Divine.

Thus, my last three visits to India were spent largely clinging to the gates outside his cottage at Manapakkam, Chennai, or wherever he travelled. I was miserable in my craving to be near, but still joyful to glimpse him from afar.

But I never appreciated, until long after, how much he was teaching me by his absence, just as he had earlier taught me by his presence. The lessons of absence were hard lessons, but they were necessary as the built-in barzaks or obstacles that Babuji said were a natural part of anyone’s spiritual yatra or journey.

Finally, a liver transplant in 2012 and dwindling funds kept me put in New Orleans, far from Master, though I tried as best I could to stay close via almost daily emails. My old friend Depression gradually returned like a silent creeping shadow, and this time it came on deeply and hard as ice.

I went back into seclusion, into isolation, into the longest “Powell Outage” of my life. This Outage lasted twelve years, from February 2013 to April 10, 2025. That’s when I awoke on my sagging old couch and discovered that my body was tingling from a surprise dream-visit by both Daaji and Chariji.

That dream ended my twelve-year isolation and returned me to the work I believe I was born for. It also quite literally saved my life, because a week later on Maundy Thursday, I was in an ambulance back to the hospital after a severe thyroid condition put me close to what’s called a myxedema coma, the kind you don’t wake up from, I was told.

On April 10th, when this dream came, I was planning an exit by suicide. The first time was in Sitka, Alaska, in 1982. I won’t detail that except after a full night of agony and razor blades and a blood-filled hotel bathtub, I staggered to the window and pulled the shades to see the mountains outside.

Just at that instant, the sun broke through the peaks of a distant mountain range. Years later, as I was telling Chariji this experience in his office, I glanced above his head and saw the SRCM emblem that Babuji had designed—a sun breaking through the distant mountain peaks. My mouth fell open. Chariji smiled. All he said in a soft voice was two words, “Sahaj Marg.”

But in April of 2025, for the second time in my life, I was again planning to make my own exit from a life that seemed pointless. This time, I was going to do it in a way that nobody I left behind, my grown son especially, could be certain I had committed suicide. Because suicide leaves a big scar on the family and close friends you leave behind—I learned that from my bloodbath in Sitka.

But what if you happen to take just a little too much insulin for the diabetes I’d had (caused by tacrolimus, the drug I have to take for the 2012 liver transplant)? I still had the poetic idea from Sitka that I could, like Goethe’s Young Werther, somehow “cease upon midnight with no pain,” and this time with no one being the wiser.

Insulin, I learned, clears from the body, and lots of diabetics die from insulin overdoses, accidental and intended. Why not me?

That’s when the dream of April 10 came, and it was followed a week later by a near-fatal thyroid condition. Do you agree with me that the Master was looking out for me, maybe saying something like, “That boy is now an old man, and he has been ignoring his own body and is about to die. He still hasn’t done the work we want to take from him. Let’s visit him in a dream and wake him up.”

Because that is exactly what I think happened to me. Chariji once told me that when any holy being, in some form, appears in a dream, it is no longer just a dream. It is a visit. And each visitation has a purpose.

Daaji said that for older people, a kind of special yogic transmission is available, because there may not be much time left for us. I feel this is true because I never experienced transmission like this before. I can now feel transmission, like radio or television vibrations, flowing everywhere all the time.

Preceptors simply step down and redirect transmission, the way transformers on telephone poles step down the voltage of electricity from the high-voltage power wires connected to a source, and these transformers redirect it into individual homes at a safe, usable voltage.

How much time do we have left? Young or old, we each could die tomorrow. Even though Chariji once told me the age I would be when I died, I never really believed it until now, when I can sense much of my own neglected Work is still left undone. We’ll see.

I do know that now this journey from Isolation is at an end. The really stupid thing is that I wasted twelve years in an ego shadow-play of guilt and shame, when all the time I ignored the basics of our beautiful practice that I even wrote a book about back in 1996, but seemed to completely forget only a few years later.

All I had to do was the three simple Heartfulness practices we’re asked to do every day.

- To meditate in the morning,

- To clean in the evening, and

- To finish with the bedtime prayer and the Tenth Maxim.

The importance of prayer is often overlooked. We use prayer at the end of each day to review, repent, reset, and renew. I needed to simply reset and move on—without all the self-inflicted drama and guilt over my poor behavior around Master, and shame over my many failings. All these games are again the work of that sly and slippery spiritual ego, a game of guilt and shame that is a quicksand trap.

I believe the long, long journey from Isolation to Solitude can actually happen in an instant—just as birth does, although a long gestation is also necessary for us to be born. But birth only happens in the instant you break free from the only world your baby's body knows this time around, a dark womb-world of water.

Now, at long last, I find myself awakening each day into a state of abiding Bliss, a state of blissful gratitude. This is just what I used to read about in holy books and what I heard about again and again at the feet of my Master. I didn’t know if it was true, because it was only hearsay, beyond the only thing Vivekananda said that counts in any spiritual journey—our own direct experience.

So now, thanks to the infinite patience of my Master, whom we remember in the earthly forms of the four great Guides, I now know from my own experience that what we have heard them all say is true. What before I had only read and heard, I now know by Heart.

I know the bliss that dwells in Solitude to be my Reality.

References:

¹ Preceptor (Sahaj Marg/Heartfulness): an authorized trainer who conducts meditation sittings and offers guidance in the practice.

² Abhyasi: one who practices abhyāsa (regular, sustained spiritual practice).

³ Yogic transmission (prānāhuti): the subtle offering of spiritual energy to the heart, used in Heartfulness to accelerate inner transformation.

4 Gurukulam: a traditional system of learning based on close, lived association with a teacher (guru).

5 Mission: the Shri Ram Chandra Mission (SRCM), a global nonprofit organization that preserves and disseminates the Sahaj Marg (Heartfulness) system of meditation and spiritual practice.

6 Lalaji Maharaj: Shri Ram Chandra of Fatehgarh (1873–1931), affectionately known as Lalaji, revived the ancient art of yogic transmission and was the first spiritual guide in the Heartfulness tradition.

7 Babuji Maharaj: Shri Ram Chandra of Shahjahanpur (1899–1983), revered in the Heartfulness tradition as the second spiritual guide and founder/first President of the Shri Ram Chandra Mission.

8 Daaji: Kamlesh D. Patel is the current spiritual guide of the Heartfulness movement and president of the Shri Ram Chandra Mission.

9 Bhaisaheb: an honorific combining bhai (brother) and saheb (respected elder), used as a term of loving reverence.

Clark Powell

Clark Powell is first a poet. An award-winning columnist, he has been published in Southern Living, Yoga International, and regional newspapers. He is the author of Sahaj Marg Companion. C... Read More